…as region experiences troubling reversals

By the early 2000s, West Africa appeared to be turning a corner. Multi-party elections had replaced decades of authoritarianism, regional bodies were championing democratic norms, and coups, once a familiar feature, seemed to be fading into history. But two decades later, the region is experiencing an unsettling reversal.

From Mali (2020, 2021) to Guinea (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and most recently Niger (2023), military takeovers have returned with a vengeance, raising concerns that West Africa may be sliding into a new era of instability. The persistence of these coups does not simply signal the fragility of democratic institutions; it represents a broader crisis; one intertwined with governance failures, insecurity, economic hardship, and disillusionment among citizens.

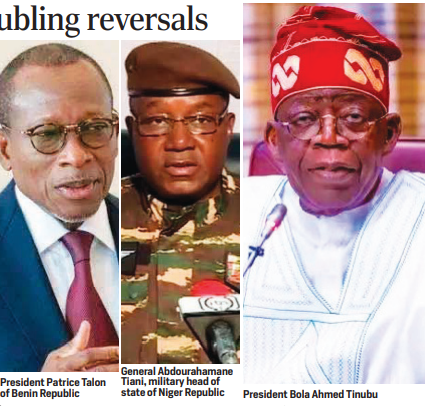

However, what could have become another military takeover in Benin Republic was thwarted by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), led by Nigeria, after mutinous soldiers struck in the country on Sunday, December 7, 2025. As ECOWAS, the African Union, and global actors scramble for solutions to military coups in the region, the question remains: How can West Africa break this dangerous cycle? The new coups are not like the old ones, unlike the ideologically driven coups of the 1960s–1980s, the latest coups are emerging from a complex mix of national frustration and regional insecurity.

In countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, the military capitalised on public anger over rising jihadist violence. In Guinea, anger over constitutional manipulation fueled popular celebrations of the junta’s takeover. These coups share several traits: public support, at least at the beginning. Many citizens now see military intervention as a relief from corrupt or ineffective civilian leaders.

Streets that once filled with protest against coup plotters now fill with celebration. Security as justification; juntas claim they are restoring order and fighting terrorism, a message that resonates in Sahelian states ravaged by extremist attacks. Anti-Western rhetoric: Russia’s growing influence and messaging have reshaped public opinion.

Many coup leaders have adopted anti-French or anti-Western positions, finding safe narratives in sovereignty and nationalism. A fading fear of sanctions: ECOWAS sanctions, which once deterred coups, are increasingly seen as ineffective, or even counterproductive by populations suffering under already harsh economic conditions. Junta leaders now calculate that they can survive or out manoeuvre regional pressure. Why the region is vulnerable: Elections are held, but democratic culture remains shallow.

In some countries, incumbents manipulate constitutions to extend their stay in power, eroding public trust. Weak judiciaries, politicised security forces, and fragile parliaments create fertile ground for military opportunism. Worsening economic conditions: Rising inflation, unemployment, poverty, and declining living standards have pushed citizens to desperation. In these circumstances, the military’s promise of “restoring order” can appear tempting.

Escalating insecurity: The Sahel is facing one of the fastest-growing extremist threats in the world. Civilian governments have struggled to contain violence from jihadist groups linked to al-Qaeda and ISIS. Militaries exploit this failure as justification for seizing power.

External interests and shifting alliances: Global power competition, particularly between Western nations and Russia, has created new incentives for coups. The Wagner Group’s presence in Mali and Burkina Faso has boosted junta confidence and provided political cover.

ECOWAS at a Crossroads

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) once had a reputation for decisively confronting coups, as seen in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and The Gambia. But today, the bloc is facing its toughest test.

Why ECOWAS is losing its influence:

Inconsistent responses: Harsh sanctions on Niger, but softer approaches in Guinea and Burkina Faso have fueled accusations of bias. Loss of trust: Citizens increasingly view ECOWAS as protecting political elites rather than defending democracy.

Internal fractures: Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger’s joint withdrawal from ECOWAS in 2024 weakened regional unity. Limited military options: The domestic climate in member states makes military intervention politically risky. ECOWAS must now decide whether it will reinvent itself, or continue losing relevance.

What went down, the coup attempt in Benin Republic

In the early hours of Sunday, December 7, 2025, a group of mutinous soldiers in Benin (calling themselves the Military Committee for Refoundation) seized key state installations, including the national television station and a military camp. They appeared on state TV, declared the government dissolved, and announced that they had removed the President from power. The putschists also reportedly attempted to attack the presidential residence and targeted senior military officers.

How the coup was foiled — Nigeria’s role, regional response

Following a formal request from Beninese authorities, Nigeria deployed its Air Force. Fighter jets entered Benin’s airspace and carried out precision airstrikes to dislodge the coup plotters from their strongholds, notably the TV station and the occupied military camp. After air operations, Nigerian ground forces entered Benin in sup- port of loyalist Beninese troops to secure strategic points and restore order.

The ground and air operations successfully blocked escape routes for the mutineers. Several suspect- ed plotters were neutralised or captured; armoured vehicles used by coup elements were immobilised or destroyed. By Sunday afternoon, the situation was declared under control. The legitimate government regained hold of the state, key military installations, and the capital.

Regional/international backing; why this intervention happened

The intervention by Nigeria came at the request of Benin’s government, which issued a diplomatic note seeking “immediate air support … to safeguard the constitutional order.” The regional bloc Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) mobilised a standby force, drawing troops from Nigeria and other member States, a move aimed at preserving constitutional order and preventing destabilisation across the region.

The coordinated effort under- scored Nigeria’s readiness to act beyond its borders when a neighboring state’s democracy is under threat, signaling that instability in one country can have spill-over effects across the region. In short, the coup in Benin was foiled because the legitimate government acted quickly, invited assistance, and got decisive cooperation from Nigeria, with air strikes, ground troops, and regional coordination, to counter the mutiny before it could gain traction.

Battling the Wave: What needs to happen

Solving the coup crisis requires more than condemning juntas. It demands addressing the structural weaknesses that make coups possible. Strengthen democratic governance: Countries must build institutions, not strongmen. Independent judiciaries, transparent electoral commissions, and accountable security agencies are essential.

Address the security crisis with regional cooperation: No country in the Sahel can defeat terrorism alone. A joint regional security force, properly funded and professionally managed, could turn the tide.

Tackle economic hardship head- on: Social safety nets, youth empowerment programmes, and economic reforms are critical to reducing the desperation that fuels support for coups. Sanction constitutional manipulations, not just coups: When leaders extend term limits illegally, they set the stage for instability.

Regional bodies must condemn constitutional coups as strongly as military ones. Engage citizens meaningfully: Civic education, community-based peacebuilding, and media literacy campaigns can help counter disinformation that glorifies military rule. Rethink foreign partnerships: African states must negotiate partnership, whether with the West, China, or Russia, that serve citizens, not political elites.

A battle for the region’s future

The resurgence of coups in West Africa is more than a political crisis. It is a threat to the region’s future; its stability, development, and global standing. But it is also an opportunity: a moment to rebuild governance systems, strengthen institutions, and restore citizens’ faith in democracy.

If democratic leaders, regional blocs, and civil society rise to the challenge, West Africa can still reclaim its trajectory. But if the region fails to confront the factors feeding coups, future generations may inherit a continent trapped in repeated cycles of military rule. The battle is far from over, but so too is West Africa’s potential.