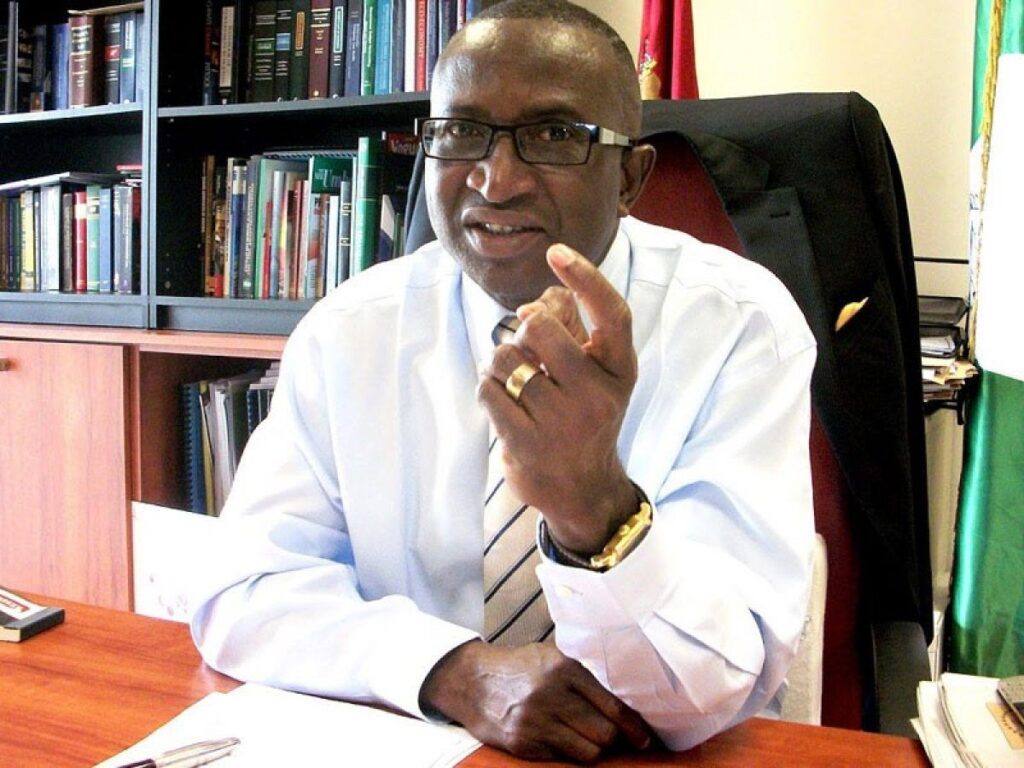

In a revealing interview on the inaugural episode of the podcast, “The Exchange,” hosted by Femi Soneye, former Senate Leader, Victor Ndoma-Egba, has painted a poignant picture of Nigeria’s journey from the hopeful dawn of independence to its current struggles, attributing the nation’s challenges to a corrosive shift in political culture and the abandonment of foundational plans.

The renowned lawyer and public servant, who will turn 70 in five months, drew from his lifetime of experience, recalling the excitement of 1960, when the economy was “one of the fastest growing in the world” and a time when the problem “was not money, but how to spend it.”

Senator Ndoma-Egba, who began his public service as a 24-year-old board member and later became a state commissioner at 26, provided a stark contrast between governance then and now.

He revealed that in the 1980s, a state had only seven to nine commissioners, a deliberate effort to cut costs but warned that such austerity came at the price of efficiency.

He illustrated this by recounting his own overwhelming workload, overseeing what would today be over a dozen ministries, and questioned whether the current focus on the cost of governance adequately balances efficiency with frugality.

The former lawmaker identified a profound “cultural” issue as the root of Nigeria’s institutional weaknesses, pointing to an excessive deference to authority and a timidity in holding leaders accountable.

He contrasted the modest lifestyles of founding fathers like Tafawa Balewa, who lived in a mud house, with the material ostentation of modern public officers.

“It’s the milieu, the environment that defines… today,” he stated, noting that his own mother, a local government chairman, walked to work without an official car or residence.

Reflecting on his tenure at the helm of the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), NdomaEgba lamented that a wellconceived master plan for the region was “abandoned almost immediately” due to “convenience” and political pressure.

He described the commission as being seen by many as a “share of the national cake,” and revealed a staggering 62-step bureaucratic process for payments that bred inefficiency and corruption.

His own attempts at reform were thwarted, including an investigation into contractors’ allegations that was violently disrupted by thugs. Shifting to the legislative arm, Ndoma-Egba, who was the first chairman of the Senate Committee on Media and Public Affairs, recalled the public’s deep-seated impatience with the National Assembly, a sentiment he linked to prolonged military rule that made the institution seem dispensable.

He cited the infamous “furniture allowance” saga, where the public narrative overlooked that the National Assembly had actually rejected a higher N12 million estimate in favour of a N3 million one, as an example of how the institution struggled with its public perception.

On a more positive note, the former Senator shared his experiences as Pro-Chancellor of the Federal University OyeEkiti (FUOYE), which he described as experiencing “supersonic speed” growth.

He revealed that the 14-year-old institution has a student population of 60,000—double that of the 50-year-old University of Calabar—and has consistently ranked as the fourth most sought-after university in Nigeria.

He credited a stable academic calendar, a wonderful host community, and a vice chancellor of “great energy” for this success. When asked about Nigeria’s vast youth population, Ndoma-Egba called it an “ordinarily an asset” that could easily become “a curse.”

He emphasised that youthfulness only becomes a national advantage if it is coupled with education, skills, and opportunities.

“We must make sure that the youths are deliberately empowered,” he urged, stressing that an educated person without opportunity is a threat to society, and that his own early opportunities were formative for his career.