African leaders are advancing plans to file a joint reparation claim against the United Kingdom for crimes committed during the colonial era.

This decision comes on the heels of the conference held on December 1, 2025, in Algiers, where African leaders, diplomats, and scholars gathered for a conference on the crimes of colonialism in Africa with tagged “The International Conference on Colonial Crimes in Africa: Towards Correcting Historical Injustices by Criminalising Colonialism”.

The meeting, focused on having colonial-era crimes “recognised, criminalised and addressed through reparations,” directly advances a resolution passed by the African Union (AU) earlier this year.

“That resolution calls for justice and reparations for victims of colonialism, building on a landmark proposal at the AU’s February summit to formally define colonisation as a crime against humanity and develop a unified continental position.

Algerian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ahmed Attaf, opened the conference with a call for leaders to follow in the footsteps of their forebears who resisted in the colonial era.

He outlined the key focus areas of the conference as demands for legal and unequivocal criminalisation of colonialism, fair compensation, and the return of stolen property.

He defined these reparations as “a legitimate right enshrined in international law and universally recognised norms.”

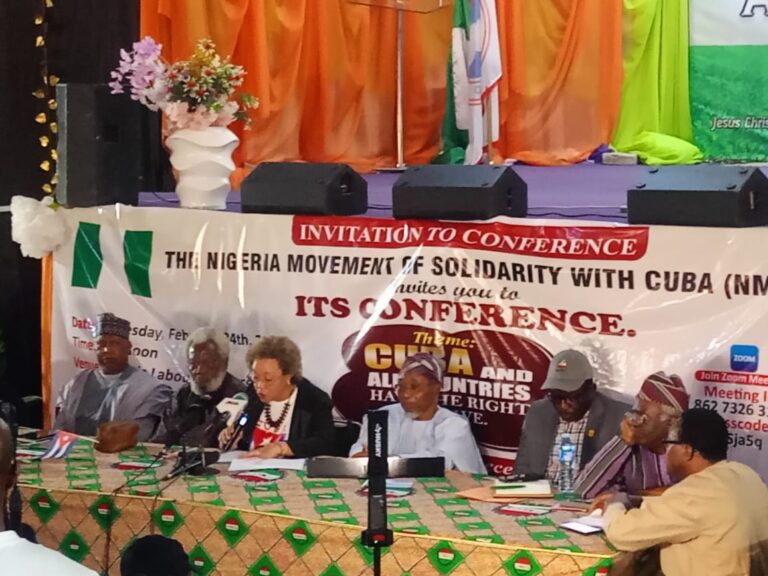

Nigeria, a regional powerhouse, is taking a leading role in the campaign. The push was foreshadowed in September when Senator Ned Nwoko sent an official claim to the British government demanding $5 trillion in reparations for the damages of colonialism. While this was a national initiative, it set a powerful precedent and figure for the broader continental discussion.

The British government has consistently rejected such claims. Officials in London have previously labelled demands for colonial reparations as “astonishingly hypocritical,” maintaining that the UK is proud of its modern partnership with African nations and refuses to engage with allegations of historical crimes in a legal or reparative framework.

However, the African initiative is gaining traction in the court of global public opinion. A recently released documentary, “From Slavery to Bond,” has renewed scrutiny of the British Empire’s legacy.

The film investigates how colonial policies on resource extraction, arbitrary borders, and historical artefacts laid a “solid ground for modern problems and crises” across the continent, lending academic and moral weight to the reparations argument.

Analysts suggest a joint AU claim would carry far greater geopolitical and legal heft than individual national efforts, posing a significant diplomatic challenge to the UK.

The next phase is expected to involve consolidating a common historical assessment, finalising a legal strategy, and determining the structure and scope of the reparations demand.