On the surface, the 2026 World Customs Organisations Technology Conference in Abu Dhabi in the last week of January 2026, followed a familiar script. Flags, formal sessions, carefully worded speeches.

But beneath the choreography, something more consequential was unfolding. As customs chiefs and trade officials compared notes on the future of borders, Nigeria arrived not with theory, but with a working proposition.

The Nigeria Customs Service Modernisation Project, being implemented via Trade Modernisation Project (TMP) Limited, unveiled to a global audience of customs administrators and policy leaders a window into how Africa’s largest economy is addressing a notoriously difficult challenge: reforming the machinery of trade while it is still running.

For decades, customs reform was treated as a technical exercise. Frequent patches here, shoddy fixes there; new software here, revised procedures there. Nigeria’s presence in Abu Dhabi was different.

Trade Modernisation Project (TMP) Limited, working with the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS), championed the view that trade is a key component of economic development requiring organic, sustainable partner ecosystems. This ensures speed and trust, revenue and credibility, and secure borders without stifling commerce.

That argument resonated in a room increasingly conscious that global trade is no longer defined solely by tariffs and treaties, but by data, interoperability, and the quiet efficiency of systems that work.

The annual Technology Conference, convened by the World Customs Organization, has in recent years become a barometer for where trade governance is heading. This year’s conversations reflected a shared anxiety. Supply chains are more fragile, Compliance risks are higher, and governments are under pressure to collect revenue without discouraging investment. Customs administrations sit at the intersection of all three.

Nigeria’s response, however, has been to attempt a full reset.

At the centre of the reform is the Nigeria Customs Service Modernisation Project, being implemented through a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) arrangement with Trade Modernisation Project (TMP) Limited as the Concessionaire. The project is designed to replace fragmented technology interventions and manual processes within the Nigeria Customs Service.

This is anchored on B’Odogwu, a Unified Customs Management System (UCMS) that integrates clearance, risk management, payments, and interagency collaboration. The ambition is sweeping. So are the stakes.

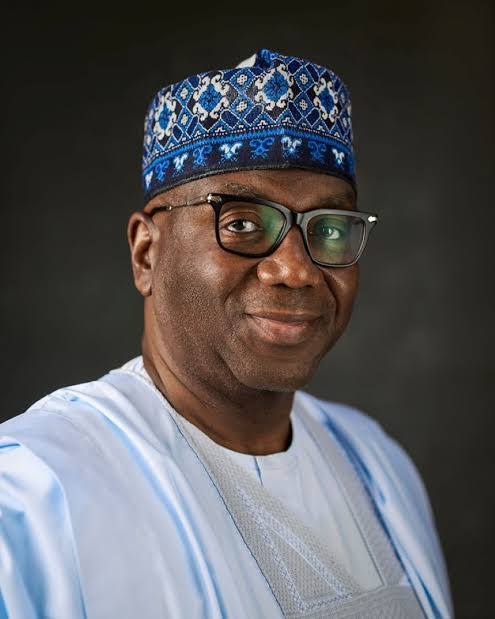

Alhaji Saleh Ahmadu (OON), the Chairman of TMP, framed the initiative as an institutional reconstruction to position the NCS at the forefront of Customs Administration technology development, aligned with global standards and assurance.

“Digital trade modernisation is not just about upgrading systems,” he told participants in Abu Dhabi. “It is about upgrading trust, predictability, and confidence in how trade flows through our borders.”

That choice of words matters. Nigeria’s economy has long been dogged by the perception gap between its size and the ease of doing business. Investors complain of delays. Traders complain of opacity. The government complains of leakages. Customs reform, in this context, becomes a credibility project.

Saleh’s message was timely and straight to the point. Modern trade demands modern Customs. Data-driven processes, automation, and risk-based controls are not luxuries. They are prerequisites for competitiveness in a world where capital moves faster than policy.

The institutional face of this digital transformation is the Comptroller General of Customs, Bashir Adewale Adeniyi, who led the Nigerian government delegation to Abu Dhabi. His message to the conference reflected a subtle but important shift in how customs leadership now sees its role.

“Customs administrations today must evolve from gatekeepers to facilitators of legitimate trade,” Adeniyi said.

“Nigeria’s Customs modernisation project reflects our determination to place the Nigeria Customs Service at the centre of national economic transformation.”

It is a familiar refrain globally, but one that carries particular weight in Nigeria, where customs revenue remains a critical pillar of public finance. “Automation”, Adeniyi argued, “is not about weakening control. It is about strengthening it through intelligence rather than discretion.”

Risk management systems reduce physical inspections. Integrated platforms reduce human contact. Data analytics improve compliance targeting. The result, if executed well, is faster clearance for compliant traders and tighter scrutiny for high-risk consignments.

In Abu Dhabi, peers from Asia, Europe, and Latin America were particularly attentive to Nigeria’s message of a new dawn for Customs Administration. Reforming customs in a small, open economy is one thing. Doing so in a market of over 200 million people, with some of the busiest ports in Africa, and the largest African economy, is quite another.

Nigeria’s presentations emphasised that Customs modernisation is embedded within a wider economic reform agenda under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, GCFR. Simplifying trade procedures, strengthening revenue assurance, and aligning with international standards are part of efforts to reposition Nigeria’s wider economy for investment-led growth.

What makes the project noteworthy is its insistence on end-to-end coherence. Rather than digitising isolated functions, the reform seeks to connect agencies, harmonise data, and reduce duplication across government in a novel all-of-government approach. It is an approach that acknowledges an uncomfortable truth: trade friction is often created not at the border, but between institutions.

The WCO 2026 Technology Conference in Abu Dhabi offered Nigeria more than a platform. It provided a stress test. Questions from peers were pointed. How will change be sustained across political cycles? How will capacity be built? How will institutionalised behaviours be unlearned?

The answers were pragmatic. Reform is being phased out. Training is ongoing. International benchmarks are being adopted not as slogans, but as operating standards. There was no claim of perfection. Only a clear statement of intent.

“Our engagement here underscores Nigeria’s commitment to international cooperation,” Adeniyi noted. “We are learning, sharing, and contributing to global conversations on the future of customs administration.”

That contribution is increasingly important. As Africa pushes to deepen regional trade under continental frameworks, customs efficiency will determine whether integration succeeds in practice or remains aspirational on paper. Nigeria’s experience, if successful, could offer a template for developing economies navigating similar constraints.

In Abu Dhabi, the mood was cautious but curious. Reform fatigue is real in many countries. Yet there was a sense that Nigeria’s effort, precisely because of its difficulty, deserves attention.

Borders are rarely glamorous. But they are decisive. In choosing to modernise their institutions in public, under global scrutiny, Nigeria is signalling something more than technical competence. It is signalling seriousness.

And in global trade, seriousness still counts.

O’tega Ogra is a Senior Special Assistant to President Bola Tinubu of Nigeria, responsible for the Office of Digital Engagement, Communications and Strategy in the Presidency.