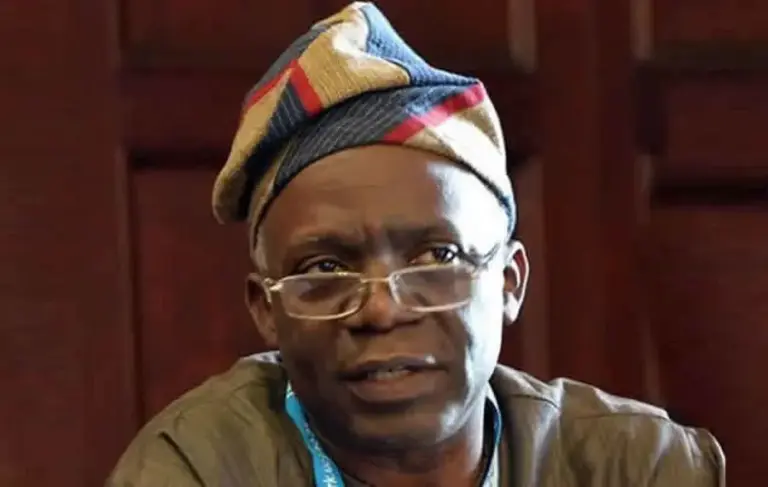

The Coordinating Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof. Muhammad Pate, has warned that Nigeria and Africa must urgently deepen investment in scientific research and evidence-based policymaking or risk being further marginalised in a rapidly changing world grappling with multiple, overlapping crises.

Pate, who said the world has entered what experts describe as a “poly-crisis” era, a period marked by simultaneous health, economic, technological, social and political shocks, stressed that only science-driven solutions could safeguard human progress and health security.

He gave the warning on Monday in Abuja at the Spark Africa Translational Research Bootcamp and Conference, organised by the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development (NIPRD) in partnership with the Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain (PVAC) and SPARK Global at Stanford University, California

The minister traced global human advancement, including gains in life expectancy and reduced mortality, to scientific inquiry and the rigorous application of the scientific method.

He said: “We are now in a world of what is called the poly-crisis, multiple contending crises all happening at once.

“Pandemics have always shifted human history, from ancient times to the last thousand years. Infectious diseases have repeatedly changed the direction of human civilisation.

“Science and scientific inquiry are so fundamental to the advancement of human societies. The advances that we see in medical science came through scientific inquiry. In just the last hundred years, we’ve seen so much progress in the quality of life of humanity overall. This is a fundamental path for human civilisation.”

Pate, however, warned that progress was fragile, noting that the COVID-19 pandemic has left deep and lingering scars on global systems.

“Countries spent enormous amounts of money to adjust to COVID-19, and that spending has left a hangover. Many economies are still struggling to get back to pre-COVID spending levels. If you look closely at today’s economic imbalances, many can be traced to the COVID disruption.”

He added that the pandemic had triggered profound structural shifts in manufacturing, labour markets, politics and technology, warning that the full implications are yet to be realised.

Reflecting on Nigeria, Pate said the country was navigating at least six major transitions at once; demographic, epidemiological, economic, technological, social and political.

“Nigeria is a very youthful country of about 230 million people and still fast-growing, yet we are also ageing in some parts. At the same time, while infectious diseases remain a challenge, non-communicable diseases now account for the largest share of our morbidity and mortality.”

The minister listed hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancers and neurological disorders as dominant emerging burdens, adding that rapid technological advances had overtaken much of what was taught in medical schools decades ago.

“What we learnt 30 or 40 years ago has been overtaken by molecular biology, proteomics, metabolomics, computing and artificial intelligence,” Pate added.

He cautioned that poorly governed technological change could erode public trust in science, citing the rise of anti-science and anti-vaccine movements.

“We now live in a world of shallow attention. People read the first two lines on their phones, form opinions and act with no depth. That environment allows anti-science movements to thrive.”

On Africa’s place in global research, Pate described a stark paradox, saying, “Africa is 1.4 billion people, yet it accounts for an insignificant portion of the global economy and an even smaller share of scientific research. Less than one or two per cent of global research spending comes from the continent, and much of that is externally funded.”

He warned that without deliberate local investment, Africa risks becoming merely a site of data and knowledge extraction, as it was for centuries with labour and resources.

“For over 400 years, Africa has been a place of extraction. Now we riskthe extraction of data and knowledge unless we do something about it.”

Pate said the Health Sector Reform Investment Initiative unveiled by President Bola Tinubu provides a framework to reverse the trend through stronger governance, research regulation and evidence-based policy.

“We are moving away from faith-based policies to evidence-based policies. You cannot pray your way through it. You cannot hope your way through it. You need discipline and scientific inquiry.”

Director-General of the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development (NIPRD), Dr Obi Adigwe, said Africa must deliberately build its own research and innovation capacity to secure its health future.

“I want Nigeria’s research to be a model that will be copied across Africa. If leaders prioritise science and research as a catalyst for health and well-being, it will open a golden door, not just for health, but for the global ecosystem.”

Adigwe challenged African elites to embrace a culture of endowments for research into diseases prevalent on the continent.

“If diabetes runs in your family, leave funding for diabetes research. If it is sickle cell, leave funding for sickle cell research. If it is cancer, leave funding for cancer research. That is how Stanford, Oxford and Cambridge grew. Until we begin to do this here, we will not solve our own problems.”

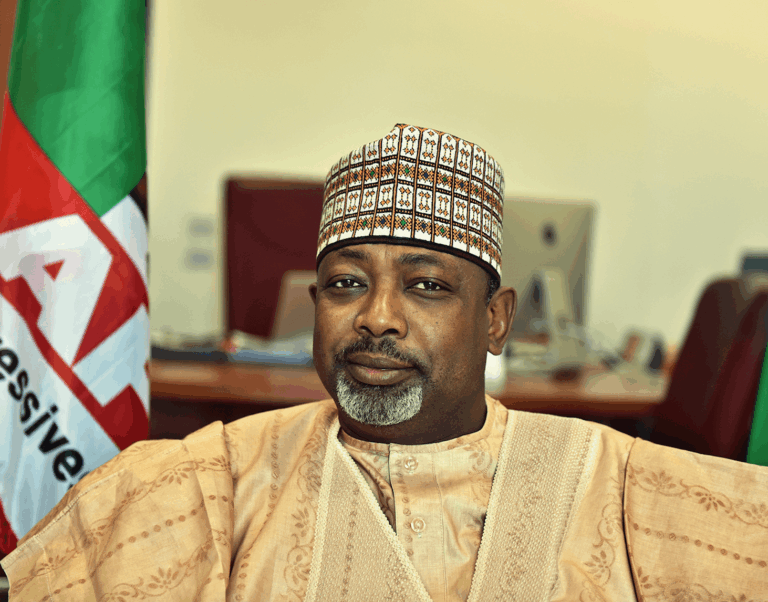

The National Coordinator of the Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain (PVAC), Dr Abdu Mukhtar, said Africa could not become a serious player in healthcare manufacturing or innovation without fixing its research and development foundation.

“You cannot move into manufacturing, into discovery, into marketing or bedside care unless you get R&D right sadly, Africa accounts for only about two per cent of global R&D spending. That has to change.”

Mukhtar said Nigeria was adopting an ecosystem approach linking research to clinical trials, manufacturing, supply chains and financing.

“Our goal is to make Nigeria the hub for local manufacturing of essential healthcare medicines for Africa but for that to happen, Nigeria must also become the continental leader in basic science research.”

From a global perspective, the Co-director of Stanford University’s SPARK Programme, Prof. Kevin Grimes, said African scientists were as brilliant as any in the world but severely constrained by resources.

“Over the last 10 years, we have met researchers across Africa, and they are every bit as brilliant as scientists in the United States. Often, they are more resource-constrained and have to work even harder.”

Grimes warned against Africa outsourcing its health research priorities, saying, “Healthcare is too important for any society to outsource its research agenda. The agenda should be set by Africans, and the products developed in Africa for Africans for security reasons and because genetics and disease profiles matter.”

He cited examples where drugs developed primarily for European populations proved less effective for people of African ancestry, underscoring the need for African-led research.

While lamenting recent cuts to international health funding by the United States government, Grimes urged African countries to pursue self-sufficiency.

“It is heartbreaking to see programmes like USAID and PEPFAR being eliminated. We must become self-sufficient. Research in Africa can and does make incredibly important discoveries. The next step is making those discoveries impactful.”

Grimes expressed optimism about the expansion of SPARK Africa and welcomed new partnerships aimed at delivering African-centric health innovations that improve lives and drive economic development.