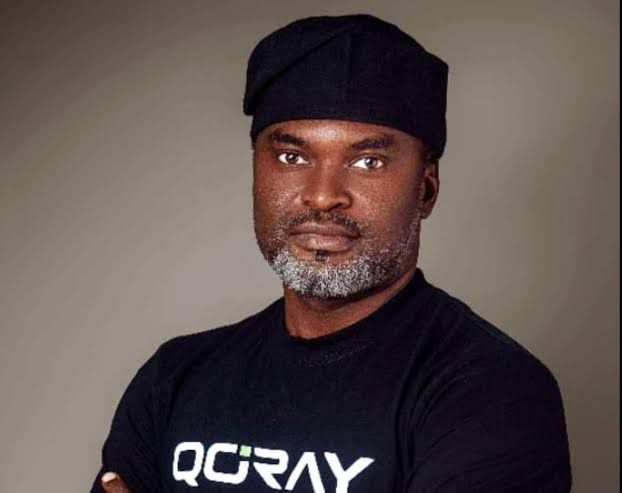

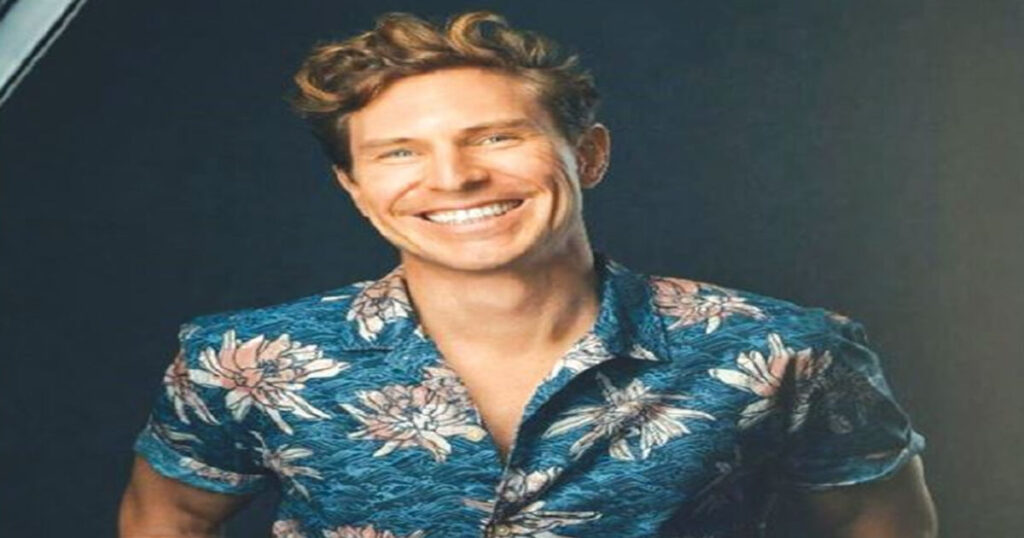

Chief Executive Officer of pawaPay, a mobile money payment aggregator, Nikolai Barnwell, speaks with FELIX OLOYEDE on the state of the African mobile payment system

How would you describe 2025 for Africa’s payments and fintech sector in one sentence, and why?

2025 was a year of regulatory maturity. Regulators have taken significant steps to clarify previously grey areas in crypto assets, foreign exchange restrictions, and licensing across the continent, from the introduction of new regulations on VASP licenses in Kenya and Ghana, to the closure of FX grey routes and the establishment of licensing regimes in the West African Economic and Monetary Union. As volumes in alternative financial infrastructure have grown rapidly, regulators sought to introduce clarity for financial institutions outside the traditional banking sector.

Looking back at 2025, what were the most important shifts in regulation and policy that shaped how fintechs and payment companies operated across Africa?

The biggest shift was increased regulatory enforcement around FX grey or parallel routes – informal channels used when official markets can’t meet demand. There are large gaps in compliant FX routes across the continent. Central bank rates in most markets are far from the parallel market rates, and access to hard currency for importers is a big issue. When central banks restrict parallel FX activity to protect their currencies, it can exacerbate dollar shortages in the short term.

Mobile money continued to grow across Africa in 2025, but unevenly. Where did you see the strongest momentum last year, and which markets struggled to move forward?

Mobile money experienced another year of strong growth, with all major wallet operators reporting increases in both user numbers and transaction volumes. West Africa, which adopted mobile money later than East Africa, has scaled usage and transaction volumes rapidly over the past year. An impressive shift was the growth of non-telco mobile money wallets in Nigeria. OPay and PalmPay have shown that mobile money wallets are no longer the exclusive playing field of telcos, putting real competitive pressure on MTN and Airtel.

Has Nigeria reached a genuine turning point in mobile money adoption, or does it still lag structurally behind markets like Kenya and Ghana?

We have seen a clear turning point in Nigeria these past 12 months. Wallets like Paga and MTN have been trying to crack the card and bank-led Nigerian markets for many years, but now we are finally seeing a massive change in user behaviour and a widespread adoption of mobile money wallets. The numbers have exploded due to the superior end-user experience these wallets bring over traditional bank and card products. There are indeed structural differences between a non-telco mobile wallet market like Nigeria and the predominantly telco mobile wallet markets of East Africa, but it would be very unfair to say Nigeria is lagging behind. They are two quite different financial infrastructures that each have their advantages and disadvantages.

Cross-border payments remain one of Africa’s toughest challenges. Based on progress made in 2025, how close is the industry to solving this problem in a meaningful way?

The main issue regarding cross-border is not a technical one. The technology is largely solved. The main constraints are liquidity and regulation. Most of the central banks fight hard to protect their currencies so their foreign-denominated debt doesn’t become unsustainable and to keep import prices from exploding. But that means that there’s a constant dollar shortage in most markets, and then a parallel market springs up where people who have dollars seek a rate at which they are willing to trade. So, it’s a difficult job for the central banks to strike a balance between keeping their currencies from sliding too fast and maintaining a flow of dollars. That’s the real cross-border payments challenge. The technical stuff is solved. There are many companies like us that have a complete infrastructure built out to transfer money instantly across borders and between currencies. But doing so compliantly is a challenge because operating compliantly often means no business at all. It’s very hard to compete with a grey parallel rate if you offer a below-market central bank rate. And the companies that do offer parallel rates are constantly balancing risk on non-compliance with short-term opportunities to serve clients. That’s the real challenge and there’s no easy fix. The only fix is to let the currencies float completely freely, but that would, in most cases, mean a very hard slide in currency strength, which would, in the short-term, cause tremendous harm to government debt and consumer prices.

A new U.S. law introducing a per cent tax on international money transfers to Africa also took effect in January 2026. What impact do you expect this to have on remittance flows, costs, and consumer behaviour this year?

You can have a personal opinion on the fairness of such a tax, but in reality, I doubt it will have a massive impact on volumes. The fluctuations and differences in FX rates are ultimately more impactful on the amount of money the recipient gets. In practice, probably a small negative effect on flows – as with all taxation – but I doubt it is enough to really move the needle.

Is there a real risk that taxes like this could push more remittance activity into informal or unregulated channels?

That risk is definitely there, but again, with one per cent, I doubt the effect will be material. A larger reason for traffic moving into unregulated channels is the control of the FX rates. Most central banks require remittances to be submitted in US dollars (or other hard currency) and exchanged at the official central bank rate. But these rates often differ by more than 10 per cent from the parallel market rates, so this obviously creates a large incentive for people to use grey routes. That has a much larger impact on the compliance of the remittance industry than a one per cent tax would have.

As we move through 2026, do you expect regulation across Africa to act more as a growth enabler or a constraint for fintechs and payment providers?

The biggest challenge with regulation is uncertainty. When regulation changes often and unpredictably, it disincentivises companies from investing and building and thus slows growth. When regulation is predictable and stable, it enables growth because companies gain confidence that the rules are set and communicated clearly, so they can seek ways to operate within that regulatory framework to create value for their customers. So, if regulators can be consistent, diligent, and communicate clearly, they can set the stage for entrepreneurs to build and grow.

Ghana and Rwanda recently announced Africa’s first fintech licence-passporting agreement. How significant is this development, and could it realistically change how fintechs expand across the continent in 2026?

This is something we are very excited to see how it actually plays out in real life. We are licensed in both Rwanda and Ghana, and we know the regulators have quite different goals and expectations in those two markets. So, it will be interesting to see how they take this from paper to real-world payment transactions. Each African market is individually small, but collectively the continent is massive and interesting. So, a challenge for fintechs is to achieve real scale or even a shot at real scale; you have to deal with a mountain of regulatory frameworks, compliance and licenses. There’s little doubt that an effective license-passporting agreement across multiple markets would give fintechs a much better chance of success.

By the end of 2026, what do you expect will be the most visible change in how Africans move money — domestically and across borders?

Stablecoins will begin to seep into everyday use, particularly through remittances into stablecoin wallets with efficient off-ramps into local currencies. Stablecoins and digital money offer too many structural advantages across the money flow to ignore. It’s hard to imagine that it won’t eventually replace traditional banking infrastructure. How much we’ll see in 2026 is difficult to predict, but if someone like WhatsApp implements a stablecoin wallet that allows all their users to instantly transfer money between each other, it will come very fast.

Finally, if you were advising Nigerian fintech founders today, what should they be preparing for now to survive and thrive in 2026?

Nigeria, and Africa more broadly, still doesn’t have access to the deep pools of risk-willing capital available in the US. It’s easy to get carried away by VCs who come in with promises of great exits and expectations of US-style start-up paths. But there’s not the same depth of funding available here, so the money dries up faster here. It’s incredibly hard to build a company that survives to profitability. VCs often do startups a disservice by blowing up valuations early on. People underestimate how hard it is to create a company that’s even worth one million dollars. It’s a lot of money. And to build something that is worth tens of millions, let alone hundreds of millions, is incredibly difficult and rare. To win, you first have to finish. And to finish, you have to stay alive. So find out what real value you can provide for the market and make your survival dependent on you doing that job well, rather than on the grace of VCs.