It is another opportunity for Nigerians to take stock in the journey of nation building as we mark the 65th Independence Anniversary of our country today, FELIX NWANERI reports

At independence from colonial rule on October 1, 1960, Nigeria held the hope of black renaissance. For the country’s founding fathers and the citizenry, it was freedom at a great cost.

However, 65 years after the British Union Jack was lowered for the Green-WhiteGreen flag at the Tafawa-Balewa Square, Lagos, it is still unfilled dreams, leaving many to wonder if the country’s independence was not opportunity mismanaged.

With an area of over 923,773 square kilometres, the largest single geographical unit along the west coast of Africa and the largest population in Africa (estimated at 230 million), Nigeria has the most envious economic profile on the African continent. It is the leading producer of crude oil and gas in Africa and 6th in the world.

But the belief at independence that Nigeria would stamp her feet in the comity of nations in a record time still remains a mirage 65 years down the line despite her huge potential due to several factors. They include ineffective leadership, unbridled corruption and ethnicism, among others, while less endowed nations that had independence at the same time, have continued to record giant strides.

Faulty structure

Though Nigeria’s fragmentation predates independence given her over 350 ethnic groups, efforts by successive administrations to cement the crack did not yield desired results. The unitary constitution/ system of government presently in place under the guise of a federal system has also not helped matters.

This explains why the clamour for restructuring Nigeria has been a recurring. Its advocates are of the view that only a peoples’ constitution will re-tool the Nigerian federalism and address pertinent national questions such as autonomy for the states; fiscal federalism to pave the way for resource control by the component units; state police and indigene ship question.

Some stakeholders have continued to query whether Nigeria should continue to operate the presidential system of government and a full-time legislature, among others, in the face dwindling resources as high cost of governance at the various levels is partly responsible for the country’s stunted development.

There are also members of a political school rooting for a return to regionalism, as according to them, the present 36-state structure is no longer sustainable. While proponents of this arrangement are of the view that proliferation of states has continued to impede the country’s development given that most of them are unviable, some individuals are still clamouring for the creation new states.

No doubt, some of the demands seem genuine given that they are inspired by the same concerns that preceded state creations – minority fears, inequality and skewed development – but the consensus is that the powers of the Federal Government should be whittled down as it seems that it is the only government in place with the 65 items it has powers on in the Exclusive Legislative List.

Despite the inherent gains of restructuring, there are some stakeholders, who believe that the call is ill-motivated. Members of this political school predicated their position on the fear of disintegration.

However, there have been efforts in this regard by successive administrations although their reports/recommendations ended up in the archives. They include the 1994/1995 Constitutional Conference (CC) by the regime of late General Sani Abacha; 2005 National Political Reform Conference (NPRC), convoked by then President Olusegun Obasanjo and the 2014 National Conference convoked by the Goodluck Jonathan administration.

Inept leadership

Nigeria’s problem had never been paucity of funds and resources, but lack of leaders with vision. This, perhaps, explains why the country has stagnated in most facets of life, with more than half of its population living below the poverty line as it takes commitment and focus on the part of leaders to deliver good governance.

It has always been the leadership question, particularly the recruitment process as it is incontrovertible that visionary and committed leadership is the principal element, which ensures that government serves as a vehicle for the attainment of the socioeconomic aspirations of the people. With a few exceptions, the circumstances that led to the emergence of most Nigerians since independence showed that they were ill-prepared prepared for leadership.

In the First Republic, Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa-Balewa, emerged as leader of government business in the parliament courtesy of an arrangement that he should hold forth for the Sardauna of Sokoto (Sir Ahmadu Bello) as Prime Minister in Lagos. Six years after, the five army majors led by late Chukwuma Nzeogwu, who drew the blueprint for the first military coup that sacked the First Republic, ended up in jail, while Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi became the surprise beneficiary of the putsch.

General Aguiyi-Ironsi was still grappling with the challenges of the bad blood generated by the coup, when a counter-coup claimed his life just six months after he assumed office and General Yakubu Gowon (then a Lt. Colonel), who was not actively involved in events until that point, was named head of state. The leader of the counter-coup, General Murtala Muhammed, later overthrew Gowon. General Olusegun Obasanjo, who took over from Muhammed after his assassination in 1976, gave a graphic details of his lack of readiness for the job in his book “Not My Will.”

He was barely out of prison over an alleged involvement in a plot to overthrow the then regime of General Sani Abacha, when he was urged to join the 1999 presidential race, which he won. Obasanjo’s second coming was however different ball game. The former military leader demonstrated that he learnt some leadership lessons after he handed over power in 1979 given the way he ran affairs of the state between 1999 and 2007 that he was in office as a democratically elected president.

For Alhaji Shehu Shagari, the first executive president of Nigeria, he only wanted a seat in the Senate before he was drafted to run for the presidency in 1979. What later became of his government, especially his inability to control some ministers in his cabinet proved that he was ill-prepared for the job. Major General Muhammadu Buhari, who was head of state between 1983 and 1985, was never in the picture of the coup that truncated the Second Republic.

Arrowheads of the putsch like General Ibrahim Babangida, later toppled him in a palace coup. Babangida went ahead to rule for eight years. He capped his reign with annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election won by business mogul, Chief MKO Abiola. Wide spread protests over the botched Third Republic forced Babangida to resign on August 26, 1993.

He, however, signed a decree establishing the Interim National Government (ING) led by Chief Ernest Shonekan. The ING was ousted three months later (November) by the then Minister of Defence, General Sani Abacha. The same story goes for late President Umar Yar‘Adua and his then deputy, Goodluck Jonathan, who later succeeded him.

The belief is that they were handpicked in 2007 by then President Obasanjo as Yar’Adua never showed interest in the presidency, while Jonathan wanted to contest for the governorship of his home state – Bayelsa – before he was picked as Yar’Adua’s running mate. As fate would have it, Jonathan became president three years into their four-year tenure following Yar’Adua’s death in May 2010. Jonathan presented himself for re-election in 2011.

He was so popular in the build-up to that election that he got a pan Nigeria mandate. But the euphoria that heralded his victory waned shortly after his inauguration over what most Nigerians described as his government’s lack of vision. This, partly explained his defeat in 2015. General Buhari, a former military ruler, who won the 2015 presidential election made history as the first to defeat an incumbent president in Nigeria’s political history.

He also became Nigeria’s second former military ruler after Obasanjo to return to the presidency through the ballot. Buhari’s return to the position he vacated in 1985, was after three failed bids. Unfortunately, not much changed during the eight years he was in power. Nigeria’s decline became more palpable than before, while Insecurity and poverty ravaged the country under Buhari’s watch.

Under the present administration of President Bola Tinubu, who succeeded Buhari in 2023, it is still the same story of despair and frustration over high-cost of living and insecurity. Tinubu, who took oath of office on May 29, 2023 as Nigeria’s 16th head of state and seventh democratically elected president, made several promises that revolve around economic reforms to tackle poverty; provision of meaningful education and jobs for the youth.

While there is no doubt that his admistration has so far implemented some bold economic reforms and rejigged the country’s security apparatus to tackle insecurity, citizens are yet to feel the impact of the President’s Renewed Hope Agenda, more than two years down the line. Those, who expressed the belief, opined that the timing and manner in which the President initiated and implemented some of his policies had not been very strategic and mass appealing, culminating in more hardship for Nigerians and severe battery for the economy.

According to them, the standard yardstick to measure the performance of any economy is the wellbeing of the people and not in the sheer size of taxes levied and revenue the government generates. They further averred that despite rebasing inflation to achieve significant drop in numbers, prices of essential commodities have not really gone down, while transportation and electricity costs remain troubling.

North/South dichotomy

Despite efforts of Nigeria’s founding fathers – Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Sir Ahmadu Bello and Chief Obafemi Awolowo – to foster unity among the people, there still exist a gulf between the country’s geopolitical divides – North and South. Citizens along the two divides have continued to view each other with suspicion.

The respective regions, at some time in the country’s history, had used threats of secession to extract concessions from the Federal Government. In 1950, the North threatened to secede if it was not granted equal representation with the South in the legislative council. In 1953, the West also threatened to secede over revenue allocation and making of Lagos the Federal Capital Territory. In 1967, the East (now the South-East and South-South) declared the Republic of Biafra in line with the tradition of using threat of secession as a political instrument.

While the nation paid dearly for the civil war that ensued – loss of over three million lives during the 30-month-old war and destruction of critical infrastructure – calls for disintegration keep reverberating across the country. The question against this backdrop is: Will balkanization solve Nigeria’s problems? Most stakeholders believe it will not as every region is bedeviled by the same contending variables as Nigeria.

Unbridled corruption

One thing that has held Nigeria back since independence is systemic and entrenched corruption. This challenge is closely linked to the leadership question, and explains why successive Nigerian leaders failed to see headship as call for service and opportunity to make positive impact. Nobel Laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka, who likened corruption in the country to cancer, once used two words – ‘hydra’ and ‘octopus’ to describe the level of graft in the country.

He said: “We have a cancerous situation; you fight one arm of corruption, another grows. A methodological name for corruption in Nigeria is hydropus.” While Soyinka may not be far from the truth as Nigeria has seen its wealth wasted with little to show in living conditions of the masses, the frightening dimension that corruption assumed of late has prompted calls for more drastic measures to combat it.

The belief is that the various anti-graft agencies – Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and Independent Corrupt Practices and other related offences Commission (ICPC) are fast losing the battle. Some of the measures that have been advocated include capital punishment given the slap on the wrist kind of judgements by the courts on several high profile corruption cases.

Poverty and Insecurity

In 2022, an estimated population of 88.4 million people in Nigeria lived in extreme poverty. The number of men living on less than 1.90 U.S. dollars a day in the country reached around 44.7 million, while the count was at 43.7 million for women. Overall, 12.9 per cent of the global population in extreme poverty was found in Nigeria as of 2022.

Sadly, the various interventionist programmes of successive administrations and even those initiated by the present administration, rather than alleviate poverty, which they were meant for, seem to have only succeeded in entrenching it. Besides issues of poverty and ailing economy, growing insecurity across the country portends a grave danger to Nigeria’s unity.

From the Boko Haram insurgency ravaging the North-East geopolitical zone to banditry and kidnapping in the North-West; farmers/herders clash in the North Central; militancy cum oil theft in the South-South and agitation for self-determination in the South-East, the picture is that of a nation at war with itself.

The Boko Haram insurgency, which is driven by Islamic extremists, has not only claimed thousands of lives and property worth billions of naira, it has turned millions of Nigerians to refugees in their own country.

Besides issues of poverty and ailing economy, growing insecurity across the country portends a grave danger to Nigeria’s unity

Across most northern states are camps for over three million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), while rebuilding efforts by the Federal Government in conjunction with donor agencies have gulped billions of naira. For bandits, majorly operating in the North-West, kidnapping for ransom and cattle rustling have turned to lucrative businesses.

In the oil-rich but impoverished South-South, sabotage of pipelines by oil thieves has become legendary. Separatist agitation in the SouthEast, on its part, has not only led to loss of lives, but the Monday’s stay-at-home directive by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) has crippled the zone’s economy.

Similarly, rising ethnic tension over activities of killer herdsmen across the country has not only exposed the heterogeneous nature of the country, but the tendency of the various ethnic nationalities towards parochial consciousness hence gradually driving Nigeria to the edge.

The conflict, which has claimed thousands of lives, is mainly as a result of disputes over land resources between mostly Muslim Fulani herders and mainly Christian farmers. Though the impact of the crisis has been more devastating in the North Central since 1999, the herders have advanced towards the southern part of the country, thereby shifting the battleground.

Flawed electoral processes

It is incontestable that a credible electoral system gives credence to the quality of any nation’s democracy. However, in the case of Nigeria, it has been a gradual descent down the hill since independence. The electoral process over time has been characterised by manipulation and violence.

A publication of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) stated that the “combination of insecurity, petro-dependency, and the need to hold or have access to the presidency, drives members of the Nigerian oligarchy to fix elections, organise political violence, constantly reshuffle alliances and avoid institutionalizing stable political parties.”

It is against these backdrops that many have repeatedly called for electoral reform in order to further strengthen Nigeria’s democracy and ensure credibility of the electoral process.

This is even as successive administrations were indifferent to implement reports of several electoral reform panels set up in the past, particularly the Justice Mohammed Uwais Electoral Reform Panel. The panel, among other recommended for the establishment of an Electoral Offences Tribunal to be saddled with the responsibility of prosecuting electoral offenders, so that the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) can concentrate its energy on conducting elections professionally and competently.

Not all gloom

Despite the myriads of problems, there is no doubt that Nigeria has made appreciable progress in in the last 65 years. Most significant is that the nation has been able to sustain its unity despite threats to its corporate existence. According to some stakeholders, this is a feat worth celebrating.

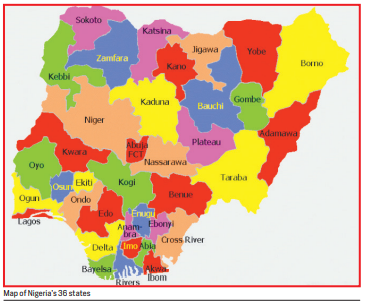

It will be recalled that at independence in 1960, Nigeria had three regions – Northern Region, Eastern Region and Western Region. A fourth region, Midwest, was later created in 1963. However, creation of states would begin in 1967 under General Yakubu Gowon’s regime. He dissolved the regions and created 12 states out of them.

They are North-Western State, North-Eastern State, Kano State, NorthCentral State, Benue-Plateau State, Kwara State, Western State, Lagos State, Mid-Western State, Rivers State, South-Eastern State and East-Central State. The number of states jumped to 19 in 1976, when the then Head of State, General Murtala Mohammed, carved out seven new states from the existing 12.

They are Niger and Sokoto from North-Western State; Bauchi, Gongola and Borno from North Eastern State; Plateau and Benue from Benue-Plateau State; Ondo, Ogun and Oyo from Western State; Imo and Anambra from East Central State. Eleven years after (1987), the regime of General Ibrahim Babangida created two more new states – Akwa Ibom and Katsina – to bring the number of states to 21.

Akwa Ibom was carved out of Cross River State, while Kastina was carved out of Kaduna State. Babangida created additional nine states in 1991 to take the number of states to 30.

The states are Adamawa and Taraba from Gongola; Enugu from Anambra, Edo and Delta from the then Bendel, Yobe from Borno, Jigawa from Kano, Kebbi from Sokoto and Osun from Oyo. The General Sani Abacha, regime which acted on the recommendations of the National Constitutional Conference (NCC) on the need for more states, created six additional states on October 1, 1996. That brought the number of states in Nigeria to 36.

The states are Ebonyi that was created from Abia and Enugu; Bayelsa from Rivers, Nasarawa from Plateau, Zamfara from Sokoto, Gombe from Bauch and Ekiti from Ondo. Other stakeholders also point to the gains of the democratic experience, which has not only afforded Nigerians the opportunity to elect their leaders at the various levels of governance since 1999, but freedom of speech associated with it. On socio-economic development, Nigeria has also made appreciable progress.

The nation did not have more than five universities at independence but it presently has more than 170 universities that include federal, states and private universities. It is the same story with polytechnics and Federal Government colleges now called unity schools. Analysts say these are testament to the fact that the nation has progressed politically and socio-economically although at slow pace compared to its peers.