Unseating an incumbent president is not something usual in African politics, but it is gradually becoming popular across the continent and beyond given growing citizens concerns over high cost of living and corruption, among other factors. FELIX NWANERI reports

Somalia was the first African country to vote a sitting president out of power in 1967, when Abdirashid Ali Shermake defeated Aden Abdullah Daar – the country’s first president (July 1, 1960 to June 10, 1967).

However, the belief at the time that the Somalian experience would lay the foundation for smooth transfer of power from one party to another did not materialize. Despite multi-party system in place in most African nations, transfer of power between rival parties has been rare.

Control state institutions by siting presidents and its attendant flow of patronage has generated a strong incumbency bias, which explains why several countries have witnessed elections without change. Record shows that only a handful of sub-Saharan Africa leaders lost re-election bids to candidates of opposition political parties during the post-colonial era.

Notable among them are Kenneth Kaunda and Rupiah Banda (Zambia); Abdoulaye Wade (Senegal); Robert Guei and Laurent Gbagbo (Cote d’Ivoire); Matheiu Kerekou and Nicephore Souglo (Benin Republic) and Denis Sassou-Nguesso (Republic of Congo).

However, the era, when incumbency plays a significant role in elections in Africa, is rapidly waning. The tempo even seems to have increased since after the historic defeat of Goodluck Jonathan by Muhammadu Buhari in Nigeria’s 2015 general election.

Before then, 88-year-old Beji Caid Essebsi, had emerged winner of Tunisia’s first free presidential poll in December 2014. He polled 55.68 per cent of votes in a run-off poll to defeat caretaker president, Moncef Marzouki, who polled 44.32 per cent, while Marzouki, who had been interim president since 2011polled 33 per cent. A veteran politician, Essebsi had led in the first round of voting with 39 per cent.

He served under President Zine el-Abedine Ben Ali, who was ousted in 2011, after the Arab Spring revolution triggered uprisings across the region. He was also in the cabinet of Tunisia’s first post-independence leader, Habib Bourguiba. The Nigerian experience, on its part, opened a new chapter in the country’s political history as it was the first time the opposition would defeat a ruling party in a presidential election.

As expected, the trend has continued to spread like hurricane to other parts of Africa. Two other sitting presidents were unseated in quick succession through the ballot after the Nigerian “political Tsunami.” They are Gambia’s longterm ruler, Yahyah Jammeh and Ghana’s John Mahama.

Both had their respective re-election bids stopped by the candidates of the opposition. Beyond the continent, the opposition has of late “seized power” even in advance democracies like the United Kingdom and United States, thereby justifying the fact that prospects for opposition’s success are not conditioned by whether or not the incumbent stands for re-election.

The year ending (2024), saw five transfers of power in Africa – Ghana, Botswana, Senegal, Mauritius, Senegal and the self-declared republic of Somaliland. Even in cases where governments did not lose, their reputation and political control was severely dented.

South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) retained power but only after a bruising campaign that saw it fall below 50 per cent of the votes in a national election for the first time since the end of white-minority rule in 1994.

This forced President Cyril Ramaphosa to enter into a coalition government, giving up 12 cabinet posts to other parties, including powerful positions such as home affairs.

The only exceptions to this have been countries where elections were seen as neither free nor fair, such as Chad and Rwanda, or in which governments were accused by opposition and rights groups of resorting to a combination of rigging and repression to avert defeat, as in Nigeria and Mozambique.

In Botswana, Mauritius and Senegal, growing citizen concern over corruption and abuse of power eroded government credibility. Opposition leaders were then able to play on popular anger at nepotism, economic mismanagement and the failure of leaders to uphold the rule of law to expand their support base.

Especially in Mauritius and Senegal, the party in power also undermined its claim to be a government committed liberties – a dangerous misstep in countries where the vast majority of citizens are committed to democracy, and which have previously seen opposition victories.

The perception that governments were mishandling the economy was particularly important because many people experienced a tough year financially as high cost of living for millions of citizens, increased their frustration with the status quo.

Besides economic hardship, defeats of some of Africa’s incumbents, this year, was informed by youth-led protests, while popular discontent over inflation played a role in the defeat of Rishi Sunak and the Conservative Party in Britain and the victory of Donald Trump and the Republican Party in the United States.

What was perhaps more distinctive about the transfers of power in Africa this year was the way that opposition parties learned from the past. In some cases, such as Mauritius, this meant developing new ways to try and protect otes by ensuring every stage of the electoral process was carefully watched.

In others, it meant forging new coalitions to present the electorate with a united front. In Botswana, for example, three opposition parties and a number of independent candidates came together under the banner of the Umbrella for Democratic Change to comprehensively out-mobilise the BDP.

A similar set of trends is likely to make life particularly difficult for leaders that have to go to the polls next year (2025), such as Malawi’s President Chakwera, who is also struggling to overcome rising public anger at the state of the economy. With the defeat of the NPP in Ghana, Africa has seen five transfers of power in 12 months.

The previous record was four opposition victories, which occurred some time ago in 2000. That so many governments are being given an electoral bloody nose against a backdrop of global democratic decline that has seen a rise in authoritarianism in some regions is particularly striking.

It suggests that Africa has much higher levels of democratic resilience than is often recognised, notwithstanding the number of entrenched authoritarian regimes that continue to exist.

Nigeria

Muhammadu Buhari, a former military, made history with his defeat of incumbent President Godluck Jonathan by 15.4 million to 12.8 million votes in Nigeria’s 2015 presidential election to become the country’s 15th head of state and sixth democratically elected president.

His victory was the first time in Nigeria’s political history that an incumbent would lose reelection bid. It was also the first time an opposition party would defeat a ruling party. The Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), which had been in power since 1999, when the country returned to civil rule, lost to the All Progressives Congress (APC) – an alliance of major opposition parties.

Buhari’s victory then also made him Nigeria’s second former military ruler after Chief Olusegun Obasanjo to return to the presidency through the ballot. Obasanjo was elected president in 1999 after relinquishing power in 1979. He had emerged in 1976 after the botched coup that claimed the life of the then Head of State, General Murtala Muhammed.

For Buhari, he returned to the seat he vacated in 1985, following the overthrow of the then military regime he headed. But it was a long road to the presidency. The journey began in 2003, when he took the first shot on the platform of the defunct All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP), but was defeated by Obasanjo of the PDP.

He was back in 2007, also on the platform of the ANPP, but was this time defeated Umaru Yar’Adua (now late), who hailed from the same state with him. In March 2010, he left the ANPP to form the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC). It was under this platform that he contested the 2011 presidential election against Jonathan but lost for the third time.

He polled 12 million votes against the latter’s 22.3 million. The intrigues and power play that characterised the election, especially the collapse of an alliance between the CPC and the defunct Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN) led by a former Lagos State governor, Asiwaju Bola Tinubu, forced him to declare at the eve of the presidential poll that he will not run for any elective office again.

He however made a detour in 2013, saying he will remain in active politics until the polity is sanitised and people enjoy the fruits of democracy at all levels of government.

His volte face, initially settled the polity but the bid for the 2015 presidency gained momentum shortly after the formalisation of the merger of leading opposition parties – ACN, CPC, ANPP and a faction of All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA), which led to the formation and registration of APC by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) on July 31, 2013.

Expectedly, Buhari’s aspiration received the endorsement of APC’s delegates at the party’s National Convention in Lagos between November 10 and 11, 2014.

He defeated four other aspirants – former Vice President Atiku Abubakar; then Kano State governor, Rabiu Kwankwaso; Imo State governor, Rochas Okorocha and the publisher of Leadership Newspapers, Sam Nda-Isaiah to clinch the presidential ticket. He polled 4,430 votes to beat Kwankwaso to the second position. The Kano State governor had 974 votes.

Atiku, who many had thought would give the former military ruler a good run, came a distant third with 954 votes, while Okorocha came fourth with 624 votes. Nda-Isaiah, a new comer to the race had 10 votes. The outcome of the primaries drew the battle line for the 2015 presidency between Buhari and Jonathan.

Though the APC leadership was able to build formidable structures across the country between 2013 the party was registered and the 2015 elections, it is incontrovertible that Buhari rode on his popularity to power, particularly in the North, where he enjoys a kind of cult-followership.

Unprecedently, Jonathan’s conceded defeat even before the final declaration of results, which marked another turning point in Nigeria’s electoral process.

Benin

It was shortly after the Nigerian experience that the opposition political party in neighbouring Benin Republic achieved a similar feat. Presidential election was held in the tiny West African country on March 6, 2015 to elect a successor for then incumbent President Boni Yayi, who was bowing out after a maximum of two five-year terms.

The first round of votes could not produce a winner and second round was held on March 20, in which businessman, Patrice Talon, an independent candidate defeated Prime Minister Lionel Zinsou of the then ruling Cowry Forces for an Emerging Benin (FCBE).

Zinsou, who was the frontrunner after the first round of voting with 27.1 per cent and was favoured to win the second round but 24 of the 32 candidates in the election, including third-placed Sebastine Ajavon, who won 22 per cent in the first round endorsed Talon, who had won 23.5 per cent in the first round, as their candidate during the second round of voting. Talon bankrolled Yayi’s successful campaigns in 2006 and 2011 but later fell out with him.

Zinsou, who was the frontrunner after the first round of voting with 27.1 per cent and was favoured to win the second round but 24 of the 32 candidates in the election, including third-placed Sebastine Ajavon, who won 22 per cent in the first round endorsed Talon, who had won 23.5 per cent in the first round, as their candidate during the second round of voting. Talon bankrolled Yayi’s successful campaigns in 2006 and 2011 but later fell out with him.

He consequently fled to France after he was accused of planning to overthrow Yayi in a coup. He only returned to the country in October 2015 after he was granted a presidential pardon. He endeared himself to young Beninese with his taste for luxury.

Many of them look up to him as being able to come up with solution for the country’s high unemployment. Reminiscent of the Nigerian experience, Zinsou, like Jonathan called Talon to concede defeat even before official release of results.

Gambia

Yahya Jammeh, The Gambia’s authoritarian president of 22 years, suffered a shocking defeat in the country’s presidential election on December 1, 2015.

He was defeated by property developer, Adama Barrow, who won more than 45 per cent of the vote. Jammeh, came to power through a bloodless coup in 1994 and has ruled the country with an iron fist ever since. He had once said he would rule for “one billion years” if “Allah willed it.”

The West African nation has not had a smooth transfer of power since independence from Britain in 1965. Human rights groups before Jammeh’’s ouster, accused Jammeh of repression and abuses of the media, the opposition and gay people.

In 2014, he called homosexuals “vermin” and said the government would deal with them as it would malaria-carrying mosquitoes. His excesses also saw him declaring the country with a population of about two million people an Islamic Republic in what he called a break from the country’s colonial past.

On voting day the internet and international phone calls were banned across the country. Observers from the European Union (EU) and the West African regional bloc ECOWAS did not monitor the process.

Gambian officials opposed the presence of Western observers, but the European Union (EU) said before the poll that it was staying away out of concern about the fairness of the voting process. The African Union (AU) only dispatched a handful of observers to monitor the exercise.

Barrow, then a member of the United Democratic Party (UDP), contested the election on the platform of Independent Coalition of Parties, He polled 263,515 votes (45.5 per cent), while Jammeh of Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC) garnered 212,099 (36.7 per cent).

Ghana

Like Nigeria, Benin and The Gambia, the opposition equally bounced back to power in Ghana, following the declaration of opposition leader, Nana AkufoAddo, as winner of the West African country’s 2016 presidential election.

Akufo-Addo, of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), won the election on his third attempt to reach the presidency, after a campaign dominated by the country’s faltering economy.

He polled 53.85 per cent of votes, while then incumbent President Mahama of National Democratic Congress (NDC) took 44.40 per cent.

As predicted then, the contest was a two-horse race between the ruling NDC and leading opposition NPP and it was the second time the candidates of both parties squared each other in four years. Mahama had earlier served as Ghana’s vice president from 2009 to 2012 before taking office as president on July 24, 2012, following the death of his predecessor, John Atta Mills.

He was elected to serve his first term as president in the December 2012 election, while Akufo-Addo, a lawyer, was Minister of Justice from 2001 until 2003 when he became Foreign Minister.

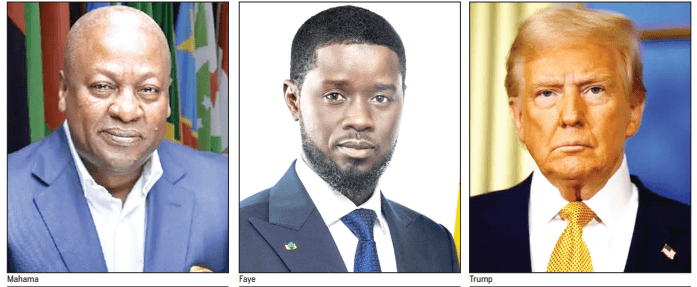

But as fate would have it, Mahama, as candidate of the opposition will return to the seat he vacated in January 2017, following his defeat of Vice-President Mahamudu Bawumia in Ghana’’s recent presidential election.

Mahaama’s victory was made possible by rising cost of living, a series of high-profile scandals and a major debt crisis that prevented the government from delivering on key promises.

Even beyond these results, almost every election held in the region this year under reasonably democratic conditions, has seen the governing party lose a significant number of seats.

This trend has been driven by a combination of factors – economic downturn, growing public intolerance of corruption and emergence of increasingly assertive and well coordinated opposition parties.

Liberia

Political veteran Joseph Boakai, in 2023, was declared the winner of Liberia’s presidential election, beating incumbent George Weah.

Boakai won with 50.64 per cent of the votes, against 49.36 per cent of the votes for former international football star, Weah, who won praises from abroad for conceding and promoting a nonviolent transition in a region marred by coups.

Weah, the first African footballer to win both FIFA’s World Player of the Year trophy and the Ballon d’Or, sparked high hopes of change in Liberia, which is still reeling from back-to-back civil wars and the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic upon his emergence but critics accused his government of corruption and failure to keep a promise to improve the lives of the poorest.

Former Nigerian President, Goodluck Jonathan, who led a mediation mission for the election, said he was “deeply pleased with the successful outcome of the democratic process.”

Botswana

It was another victory for the opposition in Africa as the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) that had ruled the country since independence in 1966 was crushed in the October 2024 general election. Besides losing power, the BDP went from holding 38 seats in the 69-man parliament to almost being wiped out.

After winning only four seats, the BDP is now one of the smallest parties in parliament, and faces an uphill battle to remain politically relevant.

Voters in the South African country delivered a shock defeat to the party that has ruled them for nearly six decades by handing victory to an opposition coalition and its presidential candidate Duma Boko.

Consequently, the 54-year-old of the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) replaced President Mokgweetsi Masisi, who on conceded defeat after his BDP lost by a landslide for the first time in 58 years.

Under the country’s electoral system, the first party to take 31 of 61 seats in the legislature is declared the winner, and can then install its candidate as president and form a government.

Mokgweetsi Masisi and his BDP ran on the slogan: Changing Together, Building Prosperity. It was the third time Boko, a human rights lawyer and Harvard Law School graduate, ran for president after contesting in 2014 and 2019. He founded the UDC in 2012 to unite opposition groups against the BDP.

Botswana, often held up as one of Africa’s greatest success stories, ranks among the wealthiest and most stable democracies on the continent. But a global downturn in demand for mined diamonds, which account for more than 80 per cent of Southern African exports, has taken a toll on the economy.

Mauritius

There was also a landslide defeat for the governing party in Mauritius in November, where the Alliance Lepep coalition, headed by Pravind Jagnauth of the Militant Socialist Movement, won only 27 per cent of votes cast and was reduced to just two seats in parliament.

With Rrival Alliance du Changemen, led by Navin Ramgoolam, sweeping 60 of the 66 seats available, Mauritius experienced one of the most complete political transformations imaginable. Ramgoolam served as prime minister from 1995 to 2000 and again from 2005 to 2014.

The poll was overshadowed by an explosive wire-tapping scandal, when secretly recorded phone calls of politicians, diplomats, members of civil society and journalists were leaked online. During the campaign, both camps promised to improve the lot of Mauritians who face cost-of-living difficulties despite robust economic growth.

Measures outlined in the Alliance of Change manifesto include the creation of a fund to support families facing hardship, free public transport, increased pensions and reduced fuel prices, as well as efforts to tackle corruption and boost the green economy. It also called for constitutional and electoral reforms including changing how the president and parliament speaker are chosen.

Mauritius, which sits about 2,000km (1,240 miles) off Africa’s east coast, is recognised as one of the continent’s most stable democracies and has developed a successful economy underpinned by its finance, tourism and agricultural sectors since gaining independence.

Both Jugnauth and Ramgoolam are members of the dynasties that have dominated the leadership of Mauritius since independence. Ramgoolam, who previously worked as a doctor and a lawyer, is the son of Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, who led Mauritius to independence from Britain.

Senegal

In the case of Senegal, the political turnaround was just as striking as in Botswana, albeit in a different way. Just weeks ahead of the election, the main opposition leaders Bassirou Diomaye Faye and Ousmane Sonko were languishing in jail as the government of President Macky Sall abused its power in a desperate bid to avert defeat.

After growing domestic and international pressure led to Faye and Sonko being released, Faye went on to win the presidency in the first round of voting, with the government’s candidate winning only 36 per cent of the votes.

Faye has won almost 54 per cent of the votes. Faye, who also became be the youngest president of the country at 44, was a relatively unknown political figure outside his party before the election. He is a senior official in the party led by popular opposition leader Ousmane Sonko.

Sonko, who was seen as the main challenger to then President Sall’s governing party, was disqualified from running for the presidency over a defamation conviction he said he was politically motivated but which authorities denied. Members of Sonko’s dissolved Pastef party and other parties formed a coalition and picked Faye as a candidate. After the two were released from jail, Sonko immediately hit the campaign trail, calling on his supporters to elect Faye.

The key tenets of the opposition’s campaign rested on the need to fight corruption in the government and to protect Senegal’s economy from the influence of foreign powers. The election also come after Sall unsuccessfully tried to postpone it, a development that sparked violent protests.

Somaliland

The opposition also won elections in Somalia’s breakaway region of Somaliland, a development that gave a boost for the region’s push for international recognition. Somaliland declared independence from Somalia in 1991 amid a descent into conflict and has since sustained its own government, currency and security structures despite not being recognized by any country in the world.

Over the years, it built a stable political environment, contrasting sharply with Somalia’s ongoing struggles with insecurity. Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi of the main opposition Waddani Party received more than 50 per cent of the votes, defeating President Muse Bihi Abdi, who sought a second term after seven years in office.

Abdullahi, 69, had served as Somaliland’s parliament speaker in 2005 and hinged his campaign on democratic and economic reforms in the region whose development has been stifled by the lack of global recognition.

Britain

Britain woke up in July this year to the scene of a political earthquake. The opposition Labour Party, after 14 years in the political wilderness handed a brutal defeat to the ruling Conservatives.

Keir Starmer was formally appointed by King Charles III as prime minister – a formality in Britain’s constitutional monarchy – swiftly replacing his Conservative Party counterpart, Rishi Sunak.

It was Charles’ first post-election prime ministerial appointment, a private meeting that typically lasts just 30 minutes. His late mother, Queen Elizabeth II, saw 15 leaders come and go during her 70-year reign. Sunak had resigned after presiding over one of the worst electoral losses in British political history.

With the counts remaining in just two of the 650 constituencies represented in Parliament, Labour had secured 412 seats, six short of its highest-ever total. The Conservatives won just 121 seats, which would be the worst result in its almost 200-year history.

The Labour Party inherits a stagnant economy, crumbling public services, rising child poverty and homelessness, and a National Health Service that, though taxpayer-funded and beloved, has become decrepit and dysfunctional.

However, many voters were said not to have been motivated by love for Labour but rather by a desire to punish the Conservatives for 14 years of scandals and policy missteps.

Labour victories, especially landslides, are rarities in British politics, which has been dominated by the Conservative Party since World War II. Throughout its 120 years, Labour has been in power for only a little over 30 of them. And since the war, only three of its leaders have beaten the Conservatives, the last of them Tony Blair, in 2005.

United States

In a stunning comeback from his loss to President Joe Biden in 2020, former Unites States president, Donald Trump of the Republican party, defeated Democrat Kamala Harris, in the November 2024 election that shocked bookmakers.

Besides Trump’s victory, the Republicans also retake control of the US Senate and the House of Representatives. Assassination attempts, criminal convictions and a change in political opponent couldn’t stop Trump winning the poll.

He swept to a decisive victory after winning several crucial battleground states. In few weeks time, the 45th president of the United States will become the 47th at an inauguration at the US Capitol. It is the same location his supporters stormed and ransacked with a goal of stopping the certification of Joe Biden’s election on 6 January 2021.